Coronavirus - when will the economy revive?

- John Calverley

- Mar 30, 2020

- 11 min read

This post is much longer than usual but it is in two parts. The first looks at the economic outlook on the assumption that the economic lockdown in the West is lifted in May. The second explains the reasons why many epidemiologists believe that this may be possible. Alongside the human tragedy of so many dying with the virus, there is a growing social and economic cost to the lockdown. In my view, Western governments will prioritise re-starting economic activity as soon as they think health services can cope with the ongoing number of hospitalisations: They will not maintain the lockdown in the hope of eradicating the virus completely, since this is unlkely to be possible, given the spread around the world.

Europe and the US have locked in most of their citizens just in the last 2-3 weeks, following the example set by China 8 weeks before. Epidemiologists believe that it should take about 3 weeks from lockdown for the number of daily deaths to plateau and then start to come down. A few weeks after that, if the trajectory follows China’s, it should be possible to get people back to work (though there is the risk of needing another lockdown later in the year). There are signs that the same plateauing is underway today in Italy though this is not confirmed (see chart). The pattern in Italy and then, about a week later in Spain, will be key for confirming the shape of the epidemic (see full details in Part 2 below).

The supply side impact of the shutdown

The shutdown is likely to cut output (GDP) by 20-30% or even more almost overnight. Some estimates suggest Chinese output fell 50% at the height of the lockdown. This translates into 10-20% of people either laid off or retained on payroll with the help of government support (but completely idle) while another 5-10% or more of output is lost because people cannot work efficiently due to supply chain problems or practical production problems. Factories may run out of supplies while people in roles such as sales, even if not laid off, may be unable to achieve much during the lockdown.

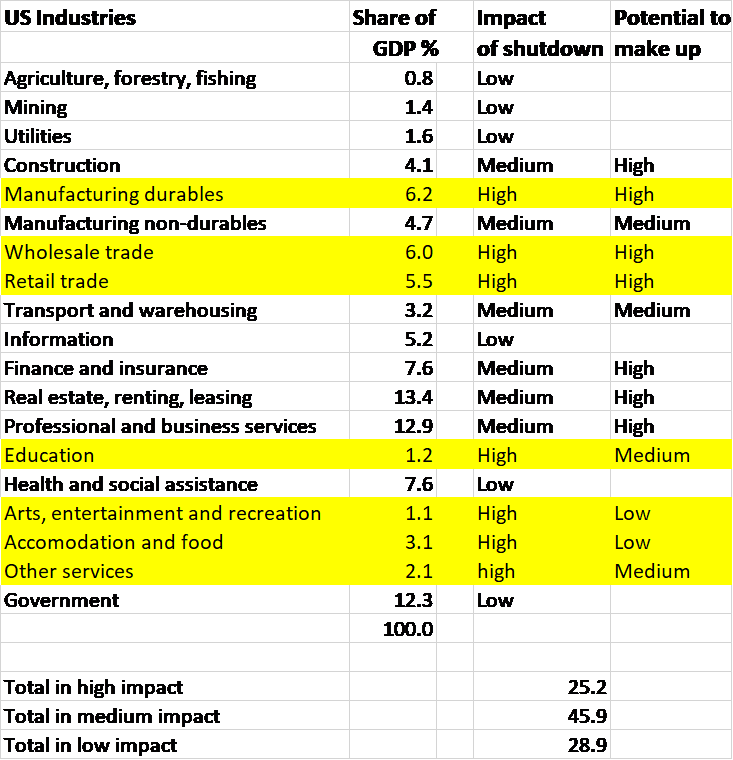

The table below takes a stab at the impact on different sectors. The two worst affected are probably ‘Arts, entertainment and Recreation’ and ‘Hospitality and food’ accounting for 4.2% of the US economy. Many businesses in these sectors are largely closed down now and are unlikely to reopen rapidly in May, as social distancing of some form may be needed for some time. Also severely impacted are wholesale and retail trade (except foods and drugs of course) and ‘durables manufacturing’, which account for a further 17.7%. In all about one-quarter of the economy is severely impacted with a further 45% moderately impacted.

The fourth column of the table considers whether the heavily impacted sectors might catch up on lost output at a later date. For example, people are not buying cars today, in some cases because they cannot get to the showroom. Once things open up car sales should rise significantly. But some people will put off buying for much longer because they have suffered a permanent loss of income or their confidence in the future is seriously dented.

Demand side impacts

The hit to income for many people means lower demand. Governments are trying to protect people with higher unemployment benefits or in-work support. But many will fall through the cracks – perhaps because they are small company owners or gig workers. Even if they get basic support or have own-resources to fall back on, their income will be down compared to usual. The same is likely to be true of retirees facing lower interest earnings and, most likely lower dividend payments, as well as lower capital values for their portfolios.

The level of the stock market makes a difference to spending in the US. A full recovery of the indices as the year progresses would definitely help with both business and consumer confidence but this is unlikely as long as the threat of a recurrence of lockdown remains.

Most companies will see a squeeze on cashflow as demand falls while fixed costs remain. Government support will help some, while others will need loans to keep going. But some companies will fail, particularly those with high debt and weak liquidity, so we should expect some high visibility ‘shock’ bankruptcies and some mergers or takeovers. Many small businesses will simply close. Meanwhile investment in new capacity will fall sharply.

Government support is big in the US and UK

Countries are putting in place massive fiscal support in the form of direct fiscal stimulus and safety net loans to businesses and households (see chart). The exact numbers are hard to pin down because some of these are novel programmes whose take-up is uncertain. To these must be added automatic stabilisers in the form of lower tax revenues and higher benefits.

The US has announced a massive Federal fiscal stimulus worth over 6% of GDP and the UK is not far behind at about 4%, while European countries have generally done much less, at least so far. The US fiscal stimulus is similar to the 5% Federal fiscal package in 2009 though it is worth noting that reduced state and local spending in 2009-10 substantially offset that stimulus. According to the IMF, China’s direct fiscal stimulus is only worth 1.2% of GDP, far less than in 2009 (about 6% of GDP) though more is expected in coming months, especially in infrastructure spending.

The 6% fiscal stimulus in the US is equivalent to 24% over a quarter. In theory, if GDP fell 24% for one quarter and then bounced back to where it started the 6% stimulus would entirely fill the income gap. It won’t work out like that of course, but there is no doubt that this is a very substantial stimulus.

There is also massive monetary stimulus with interest rates near zero everywhere in the West, important liquidity measures, especially for the dollar, the world’s investment and trading currency, as well as quantitative easing and subsidised lending. I will leave to another post the potential long-term impact of some of these measures, for example on government finances and the inflation outlook but there is no doubt that they provide both cushion and stimulus.

What to expect when the lockdown is relaxed

Let’s suppose that the lockdown in Europe and the US follows China’s path and the West goes back to work in May. I suspect the economic recovery will be neither V-shaped or U-shaped. There might be an initial fast lift as some production comes rapidly on stream, then I would expect a more gradual continued recovery. I am not sure how to characterise that shape - perhap a bit like a sloping square root sign. But this will not be simply picking up where we left off in early February and I want to highlight five key differences.

Five factors holding back a return to normal

First social distancing will most likely continue. I assume most factories and offices will return to normal output as soon as they can, using measures to reduce contact. This can be done by ensuring some people continue to work from home, by limiting travel and personal contact, by the use of videoconferencing, by physically separating groups of people so that not everybody need self-isolate if one tests positive, and by spacing out desks or machines.

And distancing is likely to remain prevalent in our social lives with restrictions on large groups, and probably still on restaurants, bars, nightclubs and sporting events. Travel and tourism may be very slow to restart. Even when these industries do re-open people will be reluctant to return and, I assume, the groups particularly at risk, a significant share of the population, will continue to shun them. In the section on epidemiology below I discuss various things which might enable social distancing to be relaxed sooner, including more testing and re-purposing of existing drugs to reduce the fatality rate in those infected, but none of these are guaranteed.

Secondly, there will be disruption of supply chains for some time. With countries emerging from lockdown at varying times the problem may be exacerbated. Think of the aftermath of the Japanese tsunami or the Thai floods but on a global scale.

Thirdly, there will be a permanent income loss for some people. It won't all be rapidly made up, as often happens with a natural disaster like a hurricane or flood.

Fourthly, there will be damage to productive capacity as firms go bust. The various loan programmes available, together with schemes where the government picks up wage bills may work for some companies but others will close for the interim and may take time to re-start while some will close for good.

Finally, there is the blow to confidence that all shocks and all recessions bring. People may be reluctant to spend as much as they could even if they have the money while businesses will be cautious about investing in new capacity.

Overall, then the economy should be looking healthier by the summer, even if our social lives are still very constrained. But it won't bounce back rapidly to February’s level. Moreover there is clearly a risk that the virus ramps up again later in the year and so the rest of this post looks at the epidemiology and particularly at the potential to tolerate a higher rate of infection in the future if the disease cannot be eradicated.

Part 2: The epidemiology

I am not an epidemiologist. Even if I were, a common saying among epidemiologists is that ‘when you have seen one pandemic … you have seen one pandemic’. In other words they are highly unpredictable even when we know the illness well, which we obviously don’t with covid-19.

Nevertheless, with that caveat there is a fairly widely held view that the number of deaths should peak about 3 weeks after the shutdown. The logic is actually simple. The lockdown itself cuts the number of new infections immediately because there is less contact. Then, with the illness progressing from infection to death in about 3 weeks on average, for the 1% or so who tragically cannot be saved, the number of deaths should peak commensurately later. (The statistics on deaths, though not perfect, are much better than the numbers for infections where the scale of testing varies widely between countries.)

This was the trajectory in China with the lockdown starting in late January and the number of deaths plateauing in the middle of February for about 10 days before declining rapidly. There are tentative signs that Italy, which locked down on the 8th March is starting to plateau now, 3 weeks on. Spain, which looks set to be the worst affected country of all, is about a week behind Italy and the rate of increase of daily deaths has slowed sharply in the last week. The UK and coastal US (New York, New Jersey are worst affected) are a further week behind, with the number of daily deaths still rising rapidly, but pointing to a peak around Easter.

There are huge caveats around this. For example, China’s lockdown was more draconian than in the West, with fewer people continuing to work. And we don’t know if different climate conditions, possible mutations of the virus or even genetic differences could change the pattern. Moreover, there remains some scepticism about China’s numbers, with many believing that the number of deaths was far higher, though this might not alter the shape of the curve. Near term, the pattern of deaths in Italy is key to watch to see whether it follows China.

After the peak, China stayed locked down for a further 2-3 weeks then began to open up the economy at the beginning of March with production gradually picking up. Wuhan, the centre of the outbreak stayed closed for a little longer. The bottom line is that, if the pattern is the same as in China, Italy and Spain should be able to let everyone go back to work by the beginning of May with the US and UK following a week or two behind. But the death rate looks like being highest in Western Europe.

How much will infections decline?

The pace of decline in infections and deaths in China might have been due to the extreme draconian measures. If you believe the numbers, China essentially eradicated domestic transmission by early March, with continuing cases only due to people flying in from Europe and the US. With measures somewhat looser in the West the decline may not be so rapid. A further caveat: the US has initially had major concentrations in New York and New Jersey with lesser ones in other coastal states. But the US has not shut the gates on these states, in contrast to the way China treated Hubei (the province containing Wuhan). So the virus may well ripple around the US, causing a long tail of disruption extending well beyond May.

Mitigating factors that could support a recovering economy

A number of developments either definitely will help, or might help, either to bring down the infection rate or to help us live with a continuing fairly high rate. One is the huge push to create more hospital facilities including intensive care beds, ventilators and PPE. If the virus recurs we might be able to live with a higher rate of infection and hospitalisation than currently, though without the help of some of the other mitigating factors following, I doubt we could just let infections rip.

A second is more and faster testing so that people can be rapidly isolated at the first signs of symptoms and their contacts also isolated. This is coming – in the West. It has been used effectively in countries such as Korea and Singapore. Initially it will be used to screen health workers but eventually it can be rolled out more generally. This could hold down the rise in infections.

A third, also coming, is antibody tests to determine who has already had the virus. There are hopes that this might reveal that far more people have caught the virus than the testing shows so far. That said, US infections, currently reported at 135000 are likely to rise to at least half a million over the whole curve in the next couple of months. But even if this number is under-reported by a factor of ten, 5 million infections would not be nearly enough for ‘herd immunity’. Even 50 million would only provide limited help in a population of over 300 million. The truth is we are nowhere near herd immunity.

A fourth mitigating factor, less certain but possibly the most important, is that trials of existing drugs, (reportedly as many as 27 different drugs of at least 3 different types) may find something that reduces the death rate from Covid-19 with acceptable side effects. There are also reports of using blood transfusions from recovered patients, which apparently was the treatment for viruses before vaccines were developed (and was used for the Spanish flu). I have not mentioned a vaccine because, even on the most optimistic view that is still at least 6 months away (most reports say a year or more) and we cannot keep the economy closed down that long.

A fifth support for opening the economy is likely to be continued social distancing by elderly and high-risk people. Perhaps they will take more risk in seeing close family but will continue to limit other contacts as far as possible.

A final possibility is the widespread adoption of masks among the general population in the West to match the ubiquitous mask-wearing in many East Asian countries. There is scepticism among scientists as to whether wearing a mask is effective in protecting people from contracting the virus. Having tried it myself I share some of that scepticism. As soon as you want to eat or drink you have to move it which is hard to do without risking infection. Or you need to use a new one but then you could get through several each day. It might be useful for workers travelling on crowded public transport to work, but they would need to use two a day. The real value may be in lessening the risk of infected people passing it on, especially since they are infectious for a day or two before symptoms appear.

What if the virus recurs?

There have already been signs of a new rise in infections in China and Hong Kong, and they are stepping back from relaxing social distancing. China closed cinemas again, having reopened them briefly. China has also closed the border to foreigners. If Western countries do this, it will make it harder for the economy to return to normal by interrupting normal commerce as well as seasonal migration of, for example agricultural workers. But if they don’t, there is a strong risk that the virus ramps up again, possibly in just a few weeks or perhaps later in the year, if there turns out to be a significant seasonal pattern (which we don’t really know yet).

At that point we will have to make a choice. Do we lock down the economy a second time? Or do we allow the virus to ramp up again, hoping that we have enough medical resources to save the people that can be saved? I don’t know the answer to this. Much may depend on whether some of the other mitigating factors listed here, particularly the repurposing of drugs, can help us. I suspect continuing uncertainty over the possibility of a renewed lock-down will be a drag factor on the economic recovery for many months. Stay safe.

Comments