Britain and Brexit

- John Calverley

- Aug 6, 2019

- 5 min read

The British economy should be riding high. True, Europe has slowed. But the US is still doing well with growth in H1 around 2.6% at an annual rate and the British economic cycle tends to be closely aligned with the US. The problem obviously is the uncertainty over Brexit. This post briefly summarises the economic situation and then looks at the likely outcome for Brexit and the economic implications of the different possibilities.

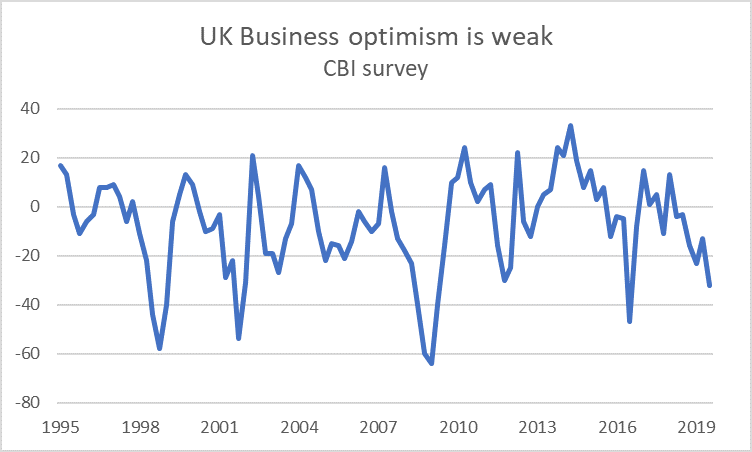

The British economy this year has stalled. Stockpiling ahead of the expected Brexit date flattered the Q1 numbers slightly and Q2 could be negative as some of this is given back. Behind this noise business is being cautious over hiring and consumers over spending and GDP is basically flat. The problem is uncertainty, with business confidence very weak and consumer confidence sagging. On the plus side for spending, wage growth has been edging up, reflecting the very full employment situation as well as fewer European workers coming in.

The impact of different Brexit scenarios

The best outcome would be an agreed deal with the EU. That would still leave plenty of uncertainty over long-term arrangements but the issue would go to the back burner for business for a while. Moreover a deal now with the EU would encourage hopes that both sides can be pragmatic. And importantly it would leave a Conservative government in place with a decent chance of securing a larger majority in the election that would soon follow. Keeping Jeremy Corbyn out.

Wouldn’t a new referendum with a decision to remain be a better outcome? This has become very unlikely now but also it would split the Conservative Party and make a Labour government more likely. Let’s consider how a referendum could happen. One possibility is that Johnson cannot achieve his aim of taking the UK out of the EU, calls a referendum for support and then loses it. An election would soon follow, with the Conservatives in total disarray.

Another possibility is that an election occurs before October 31st which the Conservatives lose. In both cases Labour would be unlikely to win outright so a coalition with the Liberals and perhaps Scottish Nationalists is the most likely. The other parties would probably reject Jeremy Corbyn as Prime Minister but even without him, business would worry about unfriendly policies.

The worst outcome for the economy is a no-deal Brexit. The impact is very hard to model, as we saw back in 2016 when most forecasters were too pessimistic on the impact of a Leave vote, at least for the short-term. That time the consumer savings rate plummeted, keeping consumer spending going despite lower real earnings due to the fall in the pound. But the savings rate is now low and this effect is very unlikely to recur.

There are 4 ways a no-deal Brexit would hurt the economy. First, there could be some short-term disruption as production lines are stopped for lack of inputs or inability to transport produce. This could have a political impact but probably not much effect at the macro-economic level. Secondly, certain businesses will close, or move people into the EU. Some of this could happen quickly, some very gradually over time. For example, City workers might have to relocate at very short notice while car production might just tail off over several years as firms invest elsewhere for the next model.

Thirdly, there is the impact which politicians don’t like to talk about much but it is what drives most of the losses in economic studies. If trade is more difficult because of tariffs, content regulations and other protections, there is less competitive pressure on British firms and over time they will become less efficient. The UK’s already dismal productivity growth will become even worse. It is not often understood that the improvements in productivity in the 1980s and 1990s, and indeed Thatcherism itself, were driven by entry to the EU which showed up how unproductive British manufacturing had become. It was entry into the EU which forced the UK to change the 1950s economic model. Management lost its cosy amateurish Britishness while unions no longer stopped workers from working with demarcation disputes, working to rule and strikes.

Finally, there are confidence effects. After 2016 confidence unexpectedly held up at first, especially among consumers, before declining over the last year. This time, confidence would probably fall immediately and then, presuming the recession is mild, pick up again. Overall, I would expect only a mild recession, with GDP falling 1-2% peak to trough, but then only a slow recovery. Slow, because the uncertainty won’t go away. The EU will still want a chunk of money and a solution for Ireland in return for a trade agreement. And the negotiation will take years rather than months. Moreover somewhere in the early months, Johnson will be trying to win an election, because he can’t continue for long with an effective majority of only 2. He might not even win, which raises the possibility of Brexit AND a Labour government.

Ranking the probability of Brexit outcomes

What is the most likely outcome? Despite the current posturing, it is still a negotiated departure, possibly with a short delay, followed by an election that Johnson wins. I put the probably of a negotiated deal at about 50%. While taking a strong stand now, Johnson is perhaps the one leader that could keep the hard Brexiteers onside when he has to compromise. And bear in mind that he, along with Jacob Rees-Mogg and Ian Duncan Smith (two of the most committed Brexiteers) all voted for the May deal on the 3rd attempt, proving they can be flexible.

In anticipation of the coming election Johnson is busy spending money in areas voters like, such as the NHS and police. The good news is that this is affordable, given the huge improvement in public finances achieved by Osborn and Hammond. And the Labour Party is divided and demoralised, with Jeremy Corbyn’s appeal much faded.

The next most likely outcome is a no-deal Brexit. Perhaps 40%. Both sides today are taking strong positions. Johnson has limited flexibility because he needs to do a deal with Farage and the Brexit Party to win the next election and they won’t cooperate if he gives up too much. Meanwhile the EU is ponderous, inflexible and unpredictable when it comes to negotiations. Much will depend on the Irish and German leaders.

I put the chance of a new referendum at only 10% today, either called by the Conservatives or more likely after Johnson calls an election and loses. Even if there is a new referendum, that does not mean the vote will be to remain. It is probably 50-50 which way it would go. Meanwhile the uncertainty would continue. And a Remain vote, probably only narrow in any case, would leave the Conservative Party in tatters. No wonder business is worried!

Comments